BULIMIA

FOODS THAT HARM

FOODS THAT HEAL

WHO’S AFFECTED

Although bulimia literally means “the hunger of an ox,” the majority of those with bulimia do not have excessive appetites

Instead, their tendency to overeat compulsively seems to arise from psychological problems, possibly due to abnormal brain chemistry or a hormonal imbalance

Despite their overeating, most of them are of normal weight

They compensate for overeating by strict dieting and excessive exercise, or by purging through self-induced vomiting or abuse of laxatives or enemas

Repeated purging can have serious consequences, including nutritional deficiencies and an imbalance of sodium and potassium, leading to fatigue, fainting, and palpitations

Acids in vomit can damage tooth enamel and the lining of the esophagus

Laxative abuse can irritate the large intestine, cause rectal bleeding, or disrupt normal bowel function, leading to chronic constipation when the laxatives are discontinued

One of the most severe consequences, however, may be an increased occurrence of depression and suicide

Nutrition Connection

Like all eating disorders, bulimia can be difficult to treat and usually requires a team approach involving nutrition education, medication, and psychotherapyAlong with addressing psychological issues, some nutritional issues can be addressed with these guidelines, under the guidance of a dietitian or a physician

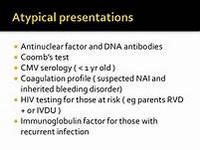

Treat nutritional deficiencies

This is especially important if the body’s potassium reserves have been depleted by vomiting or laxative abuse

High-potassium foods, such as fruits (both fresh and dried), especially bananas, and vegetables usually restore the mineral; if not, a supplement may be needed

Emphasize foods high in protein and starches

This diet should include these foods while excluding favorite binge foods until the bulimia is under control; then those foods can be reintroduced in small quantities

At this stage of treatment, the person with bulimia learns how to give himself or herself permission to eat desirable foods in reasonable quantities, in order to reduce the feelings of deprivation and intense hunger that often lead to loss of control in eating

Add high-fiber foods

Those with bulimia who abuse laxatives may need a high-fiber diet to overcome constipation

Whole grain cereals and breads, fresh fruits and vegetables, such as berries, apples, and pears, and adequate fluids can help restore normal bowel function

Beyond the Diet

A complete medical checkup is the only way to be absolutely certain of a diagnosis of bulimiaOnce certain, a doctor can offer guidance on the following: Journal

Nutritional education typically begins with asking the person with bulimia to keep a diary to help pinpoint circumstances that contribute to binging

A nutrition counselor may also give the person an eating plan that minimizes the number of decisions that must be made about what and when to eat

Treat depression

Because chronic clinical depression often accompanies bulimia, treatment usually includes giving antidepressant drugs like fluoxetine (Prozac), which also suppresses appetite, and sertraline (Zoloft)

Look at alternative therapies

Meditation, guided imagery, and progressive relaxation routines can help those with bulimia become less obsessive about weight and their eating habits

Practice patience

Don’t expect instant success; treatment often takes 3 years or longer, and even then, relapses are common

Importance of well balance diet