leukoplakia

leukoplakia

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Ulceration may be present

Leukoplakic regions range from small to several centimeters in diameter

Histologically, they are often hyperkeratoses occurring in response to chronic irritation (eg, from dentures, tobacco, lichen planus); about 2–6%, however, represent either dysplasia or early invasive squamous cell carcinoma

Distinguishing between leukoplakia and erythroplakia is important because about 90% of cases of erythroplakia are either dysplasia or carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 90% of oral cancer

Alcohol and tobacco use are the major epidemiologic risk factors

The differential diagnosis may include oral candidiasis, necrotizing sialometaplasia, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, median rhomboid glossitis, and vesiculoerosive inflammatory disease, such as erosive lichen planus

This should not be confused with the brown-black gingival melanin pigmentation—diffuse or speckled—common in nonwhites, blue-black embedded fragments of dental amalgam, or other systemic disorders associated with general pigmentation (neurofibromatosis, familial polyposis, Addison disease)

Intraoral melanoma is extremely rare and carries a dismal prognosis

Any area of erythroplakia, enlarging area of leukoplakia, or a lesion that has submucosal depth on palpation should have an incisional biopsy or an exfoliative cytologic examination

Ulcerative lesions are particularly suspicious and worrisome

Specialty referral should be sought early both for diagnosis and treatment

A systematic intraoral examination—including the lateral tongue, floor of the mouth, gingiva, buccal area, palate, and tonsillar fossae—and palpation of the neck for enlarged lymph nodes should be part of any general physical examination, especially in patients over the age of 45 who smoke tobacco or drink immoderately

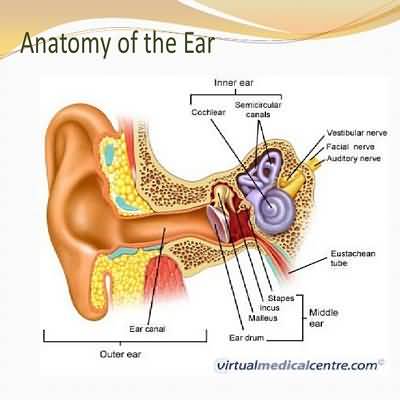

Indirect or fiberoptic examination of the nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx by an otolaryngologist, head and neck surgeon, or radiation oncologist should also be considered for such patients when there is unexplained or persistent throat or ear pain, oral or nasal bleeding, or oral erythroplakia

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy may expedite the diagnosis if an enlarged lymph node is found

To date, there remain no approved therapies for reversing or stabilizing leukoplakia or erythroplakia

Clinical trials have suggested a role for beta-carotene, celecoxib, vitamin E, and retinoids in producing regression of leukoplakia and reducing the incidence of recurrent squamous cell carcinomas

None have demonstrated benefit in large studies and these agents are not in general use today

The mainstays of management are surveillance following elimination of carcinogenic irritants (eg, smoking tobacco, chewing tobacco or betel nut, drinking alcohol) along with serial biopsies and excisions

Oral lichen planus is a relatively common (0

5–2% of the population) chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that may be difficult to diagnose clinically because of its numerous distinct phenotypic subtypes

For example, the reticular pattern may mimic candidiasis or hyperkeratosis, while the erosive pattern may mimic squamous cell carcinoma

Management begins with dis- tinguishing it from other oral lesions

Exfoliative cytology or a small incisional or excisional biopsy is indicated, especially if squamous cell carcinoma is suspected

Therapy of lichen planus is aimed at managing pain and discomfort

Corticosteroids have been used widely both locally and systemically

Cyclosporines and retinoids have also been used, but tacrolimus shows the most promise in recent studies

Many experts think there is a low rate (1%) of squamous cell carcinoma arising within lichen planus (in addition to the possibility of clinical misdiagnosis)

Hairy leukoplakia occurs on the lateral border of the tongue and is a common early finding in HIV infection (see Chapter 31)

It often develops quickly and appears as slightly raised leukoplakic areas with a corrugated or “hairy” surface (Figure 8–6)

While much more prevalent in HIV-positive patients, hairy leukoplakia can occur following solid organ transplantation and is associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection and long-term systemic corticosteroid use

Hairy leukoplakia waxes and wanes over time with generally modest irritative symptoms

Acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir have all been used for treatment but produce only temporary resolution of the condition

It does not appear to predispose to malignant transformation

Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma can be hard to distinguish from other oral lesions, but early detection is the key to successful management

Raised, firm, white lesions with ulcers at the base are highly suspicious and generally quite painful on even gentle palpation

Lesions less than 4 mm in depth have a low propensity to metastasize

Most patients in whom the tumor is detected before it is 2 cm in diameter are cured by local resection

Radiation is reserved for patients with positive margins or metastatic disease

Large tumors are usually treated with a combination of resection, neck dissection, and external beam radiation

Reconstruction, if required, is done at the time of resection and can involve the use of myocutaneous flaps or vascularized free flaps with or without bone

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma generally presents later than oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma

The lesions tend to be larger and are often buried within the lymphoid tissue of the palatine or lingual tonsils

Most patients note only unilateral odynophagia and weight loss, but ipsilateral cervical lymphadenopathy is often identified by the careful clinician

While these tumors are typically associated with known carcinogens such as tobacco and alcohol, their epidemiology has changed dramatically over the past 20 years

Despite demonstrated reductions in tobacco and alcohol use within developed nations, the incidence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma has not declined over this period

Known as a possible cause of head and neck cancer since 1983, the human papillomavi- rus (HPV)—most commonly, type 16—is now believed to be the cause of up to 70% of all oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

HPV-positive tumors are readily distinguished by immunostaining of primary tumor or fineneedle aspiration biopsy specimens for the p16 protein, a tumor suppressor protein that is highly correlated with the presence of HPV

These tumors often present in advanced stages of the disease with regional cervical lymph node metastases (stages III and IV), but have a better prognosis than similarly staged lesions in tobacco and alcohol users

This difference in disease control is so apparent in multicenter studies that, based on the presence or absence of the p16 protein, two distinct staging systems for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma were introduced in 2018

Ongoing clinical trials are trying to determine if a reduction in treatment intensity is warranted for HPV-associated cancers