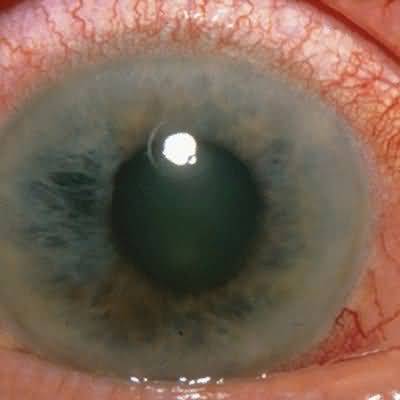

Older age group, particularly farsighted individuals.Rapid onset of severe pain and profound visual loss with “halos around lights.”Red eye, cloudy cornea, dilated pupil.Hard eye on palpation.

General Considerations

Primary acute angle-closure glaucoma (acute angle-closure crisis) results from closure of a preexisting narrow anterior chamber angle. The predisposing factors are shallow anterior chamber, which may be associated with farsightedness or short stature (or both); enlargement of the crystalline lens with age; and inheritance, such as among Inuits and Asians. Closure of the angle is precipitated by pupillary dilation and thus can occur from sitting in a darkened theater, during times of stress, following nonocular administration of anticholinergic or sympathomimetic agents (eg, nebulized bronchodilators, atropine for preoperative medication, antidepressants, bowel or bladder antispasmodics, nasal decongestants, or tocolytics) or, rarely, from pharmacologic mydriasis (see Precautions in Management of Ocu- lar Disorders, below). Subacute primary angle-closure glaucoma may present as recurrent headache. Secondary acute angle-closure glaucoma, which does not require a preexisting narrow angle, may occur in anterior uveitis, dislocation of the lens, or due to various drugs (see Adverse Ocular Effects of Systemic Drugs, below). Symptoms are the same as in primary acute angle-closure glaucoma, but differentiation is important because of differences in management. Acute glaucoma, for which the mechanism may not be the same in all cases, can occur in association with hemodialysis. (Chronic angle-closure glaucoma presents in the same way as chronic open-angle glaucoma.)

Clinical Findings

Patients with acute glaucoma usually seek treatment immediately because of extreme pain and blurred vision, though there are subacute cases

Typically, the blurred vision is associated with halos around lights

Nausea and abdominal pain may occur

The eye is red, the cornea cloudy, and the pupil moderately dilated and nonreactive to light

Intraocular pressure is usually over 50 mm Hg, producing a hard eye on palpation

Differential Diagnosis

Acute glaucoma must be differentiated from conjunctivitis, acute uveitis, and corneal disorders

Treatment

Initial treatment is reduction of intraocular pressure

A single 500-mg intravenous dose of acetazolamide, followed by 250 mg orally four times a day, together with topical medications is usually sufficient

Osmotic diuretics, such as oral glycerin and intravenous urea or mannitol—the dosage of all three being 1–2 g/kg—may be necessary if there is no response to acetazolamide

Primary

In primary acute angle-closure glaucoma, once the intraocular pressure has started to fall, topical 4% pilocarpine, 1 drop every 15 minutes for 1 hour and then four times a day, is used to reverse the underlying angle closure

The definitive treatment is laser peripheral iridotomy or surgical peripheral iridectomy

Cataract extraction is a possible alternative

If it is not possible to control the intraocular pressure medically, the angle closure may be overcome by corneal indentation, laser treatment (argon laser peripheral iridoplasty), cyclodiode laser treatment, or paracentesis; or by glaucoma drainage surgery as for uncontrolled open-angle glaucoma

All patients with primary acute angle-closure should undergo prophylactic laser peripheral iridotomy to the unaf- fected eye, unless that eye has already undergone cataract or glaucoma surgery

Whether prophylactic laser peripheral iridotomy should be undertaken in asymptomatic patients with narrow anterior chamber angles is mainly influenced by the risk of the more common chronic angle-closure

Secondary

In secondary acute angle-closure glaucoma, additional treatment is determined by the cause

Prognosis

Untreated acute angle-closure glaucoma results in severe and permanent visual loss within 2–5 days after onset of symptoms

Affected patients need to be monitored for development of chronic glaucoma

When to Refer

Any patient with suspected acute angle-closure glaucoma must be referred emergently to an ophthalmologist

No symptoms in early stages

Insidious progressive bilateral loss of peripheral vision, resulting in tunnel vision but preserved visual acuities until advanced disease

Pathologic cupping of the optic disks

Intraocular pressure is usually elevated